For centuries leaders in government, business, and professions were men; women were regarded as unfit for leadership. We are cognizant of ‘the glass ceiling’ that subtly hampers the advancement of women in politics, business, education, religion, or the law. In our time, there are efforts to correct the gender imbalance of power and end discrimination based on gender. However, there may be more important reasons for promoting female leadership than fairness: Women leaders tend to operate with a perspective, focus, and process which differs from that of male leaders. Although characteristics of excellent leadership are not exclusively male or female, our history and traditional ways of raising children have shaped our expectations of how leadership is exercised. Some examples of women leaders who changed our society:

Emily Murphy, Canadian women's rights activist, jurist, and author.

In 1916, Emily Murphy, a journalist, and activist became the first female magistrate in Canada and the British Empire. On her first day on the job she was told by a defense lawyer that she had no jurisdiction to hear his client’s case because under the 1867 founding constitution she was not “a person”. Nevertheless, Mrs. Murphy retained her position for fifteen years and became the leader of the” Alberta Famous Five” women who successfully fought even Canada’s Supreme Court ruling against them before a 1929 decision of the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council in London agreed that women are persons and therefore eligible to sit in the Canadian Senate. Emily Murphy fought for the rights of women, looked at what underlies the law to advocate for the plight of prostitutes, and worked to obtain just treatment for immigrants and orphaned children. Emily was undeterred by opposition or ridicule and exhibited unremitting tenacity in her efforts to act with justice and love for the disadvantaged members of society.

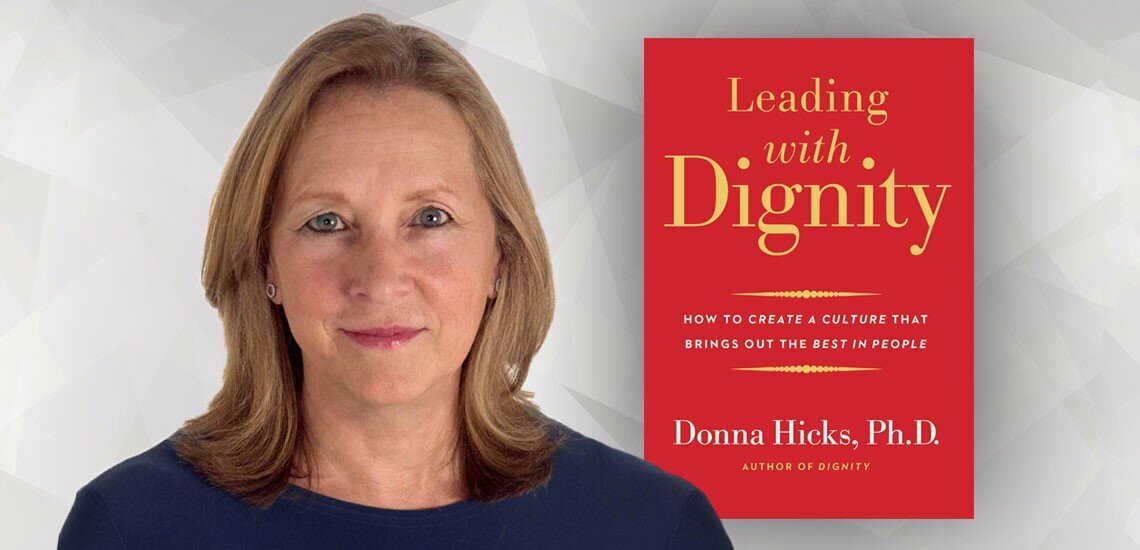

Donna Hicks is an Associate at the Weatherhead Center for International Affairs, Harvard University.

Donna Hicks, a psychologist, and leader in the field of international conflict was often the sole female member of conflict negotiation teams attempting to bring warring countries together. Whereas men generally focus on logic power and structures, Dr. Hicks focused on violations of human dignity and resolving the unhealed wounds which block exposing vulnerability and prevent open communication and resolution of differences. Yet, this soft power and awareness of the human need to be treated with dignity are far more successful than negotiating from a stance of power. (See Donna Hicks. Dignity. Yale University Press, 2011).

Florence Nightingale, OM, RRC, DStJ was an English social reformer, statistician, and the founder of modern nursing.

Florence Nightingale, who was in charge of nurses in the Crimean War, was a formidable activist who brought about the reform of hospitals, medical care policies, and nursing in the late 1800s. Jeanne Mance was the first nurse in New France and the founder of the first hospital in Canada: Hotel-Dieu de Montreal in 1645. Women, in particular, religious communities of women were leaders in founding hospitals, schools, and social services to care for the poor prior to governments taking responsibility for these services. Dorothy Day, a radical Catholic activist, journalist, and founder of the Catholic Worker movement was cited by Pope Francis in his visit to the United States in 2015 as one of four great Americans (along with Abraham Lincoln, Martin Luther King, and Thomas Merton). Yet Dorothy Day, who was endorsed for canonization, was at odds with the Catholic hierarchy, e.g., in her defense of the union of cemetery workers in opposition to Cardinal Spellman of New York, and in her criticism of Cardinal McIntyre and some priests of Los Angeles about their lack of support for human rights. She was repeatedly jailed because of her active stance of pacifism and opposition to the atomic bomb during WWII. And it is interesting to note that three countries with women leaders, New Zealand, Germany, and Iceland, were remarkably successful in dealing with the coronavirus pandemic.

So, I ponder, How do great women leaders tend to differ from the leadership of men? Some observations:

Women leaders tend to focus their attention and efforts on behalf of those who are poor, sick, deprived, rejected, and needy rather than on building economic wealth or protecting one’s ego.

Women leaders are more inclined to work collaboratively rather than competitively. They are more sensitive to how words and actions impact others and include this emotional content in the process of making decisions. Male leaders tend to focus on logic and overlook emotional wounds which may constitute hidden barriers to open communication.

Women leaders, as noted above, displayed courage and tenacity in seeking justice in the face of opposition, or ridicule.

If we want society to change, we need to have more women leaders in places where they can influence governments, religious institutions, business, law, and social structures.

-Sister Patricia McKeon, csj